We have only one story. All novels, all poetry, are built on the never-ending contest in ourselves of good and evil.

John Steinbeck

Every time someone tells a story and tells it well and truly, the gospel is served.

Eugene Peterson

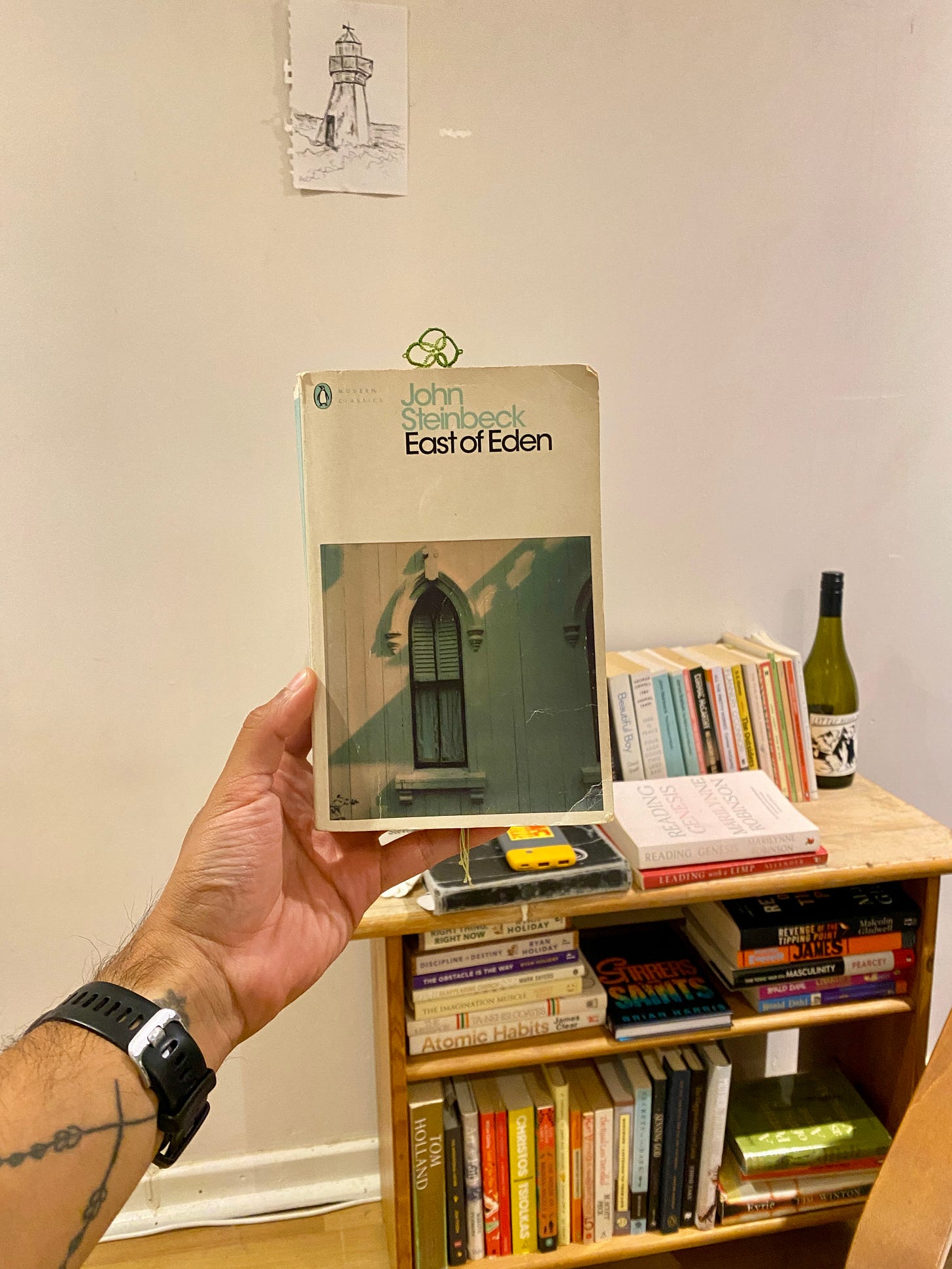

“There is only one book in a man,” wrote John Steinbeck about his great novel, East of Eden. He had already published Grapes of Wrath (1939) and many other best-selling novels and established himself as a renowned writer, but Eden would become his magnum opus, his one book.

East of Eden unfolds over generations and trials, blood and brutality, beauty and glimpses of hope. Eden is a slow burn, telling the stories of two families, the Trasks and the Hamiltons. Eden is Steinbeck’s attempt at rewriting both the story of his family and paralleling the book of Genesis in novel form.

In his own words, East of Eden is truly a book about the greatest story ever told, that of “good and evil, of strength and weakness, of love and hate, of beauty and ugliness1.”

And every year, since 2019, I re-read this wonderful masterpiece.

It was the first book that taught me to read. To savour and sit and wrestle with a story. To read not for information or data retention, but to lose time in a world not my own and gain my soul.

I read it every year, not as a chore but as a labour of love. Hoping that each time I feel something that I missed before. I start slowly - 5/10 pages before bed over a couple of weeks, then boom, it gets me and I can’t put it down.

In many ways, I return to East of Eden every year because I must. It’s a tall, cold glass of water for my parched soul. Amid brain rot and YouTube and getting caught up on all the junk I don’t have or need – this novel pulls me back to the greatest Story being written. The great novelists do that.

Through words and rhythm, Steinbeck offers a slow revolt against the “shallow efficiency” that floods my daily life.

We are constantly bombarded with billboards, ads, and reels promoting a quicker, better body or daily routine. But fiction writers wake us up to the “infinity of meaning within the limitations of the ordinary person on an ordinary day2.”

In other words, fiction helps us begin to see the stranger on the bus, our local barista, or the homeless foreigner as unfolding stories and symphonies instead of nuisances on our commute to work or statistics on Channel 5 news.

It is also the book that taught me to approach scripture differently, again, not for information but to embrace the Story. To pay attention to what the writers were saying through all that they were not saying.

Sometimes in the quest for answers, or a tick on my morning quiet time, I miss the Story. I think that if I have the right empirical evidence, then I’d see all of life, faith, and God correctly. But that’s not how we’re wired, we are complex creatures, you and I.

For instance, I take my physical health seriously, and I know objectively that Maccas holds little to zero nutritional value, but did I drive myself there the other night for a late-night quarter pounder and fries? Maybe! Don’t judge me.

Now, I love nonfiction and books of theology and biblical commentaries, and biographies, but they can only get me so far.

But stories, they get past my fixation with numbers and reason and mastery. Novels help me move beyond my obsession with control and into the waters of mystery and imagination.

And the best storytellers help us ask ourselves which stories we’re living out, which stories we’ve embraced, and which stories we’d long to live.

Sadly, many of us don’t even know where to start with stories. But novelists and novels are a great place to start.

For novelists, help “[re]train the imagination” to take in “everything around us and realise that it is worth the attention” of God the grand Author3.

If you’ve never been a reader, maybe don’t jump into Infinite Jest or Middlemarch or Don Quixote.

Read Tomorrow, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow or The Old Man and the Sea, or if you want to try Steinbeck (which I would highly recommend), start with Of Mice and Men.

No matter where you start, start where you can.

Because fiction is a much-needed balm. Fiction teaches us first slowly how to enter stories, how to embrace and observe and reflect. And if we allow it, ultimately, it may teach us to live richly.

John Steinbeck, Journal of a Novel, (New York: Penguin, 1990), 3.

Eugene Peterson, “Novelists, Pastors, and Poets,” in Subversive Spirituality, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 175.

Peterson, “Pastors and Novels”, in Subversive Spirituality, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 189.

Thanks for a great post. Love the Peterson quote.