But I received mercy for this reason, so that in me, the worst of them, Christ Jesus might demonstrate his extraordinary patience as an example to those who would believe in him for eternal life1.

Paul, An Apostle

Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.

Bryan Stevenson

There is a moment in Bryan Stevenson’s memoir Just Mercy, where he defines his working philosophy as a lawyer and activist:

“Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done2.”

Stevenson is a lawyer turn advocate in fighting against the unjust prison system in the United States, specifically for people on death row, youth being tried as adults and those who have fallen prey to a broken and evil penal system.

In serving those pummeled by a broken judicial system Stevenson is committed to resurrecting “language of mercy and redemption into American culture3.”

“Love is the motive, but justice is the instrument,” opens Stevenson, quoting the late theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. You see, what has fuelled Stevenson’s life and work is not hatred but love, not vengeance but justice, and not malice but mercy.

At the heart of Stevenson’s work is a deep understanding that true, prophetic equality and change can only come from proximity, “we cannot make progress in creating a more just society… if we allow ourselves to be disconnected from the people who are most vulnerable – from the poor, the neglected, the incarcerated, the condemned4.”

In other words, mercy is at the heart of transformation. Mercy is not an abstract concept but takes on flesh and blood and moves toward the most seemingly undeserving of us.

This mercy is also at the very heart of the tattered, passionate, pastor named Paul writing to his son in the faith in his final years on mission. Or the letters otherwise known as 1 and 2 Timothy.

Papa Paul

While Paul was nothing less than one of the most important figures of history whose writings have helped shape much of Western Christianity, he was also a pastor—and a loving one at that.

This is perhaps most on display in his letters to Timothy, where we hear the heart of a loving and wise father. A father that knows the contours of his son’s heart, doubts, and calling.

Paul was maybe in his early 60s, Timothy in his late 20s or mid-30s and timid in his call, needing constant affirmation and reassurance5. And in the Timothy letters, we get a first-hand account of these conversations between a young pastor and his wise mentor.

Paul longs to see his son in the faith - to encourage him and remind him that in Christ he is and has enough to go the distance in this marathon of faith.

He also is reminding young Timothy to take care of his tummy troubles:

No longer drink water exclusively, but use a little wine for the sake of your stomach and your frequent ailments (1 Timothy 5:13).

So what is the animating and anchoring force behind this father/pastor’s care for his son? Verse 14 cues of letter one cues us in on this. Paul writes:

The grace of our Lord was poured out on me abundantly, along with the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus.

The very essence and reality of Christ pulsating in Paul’s heart, mind, and pen is the force behind his compassion and love for Timothy.

Paul has wrestled with his discouragement, sin, and pain and he’s come to believe in the depths of his guts - not in his gifts, genius, or talents - but in the work of Jesus.

Paul, the worst among us was shown grace and mercy. He, and now we, not only scrape by into this life with Christ but are made abundantly alive by this never-ending mercy. This mercy bleeds across nearly every page of these letters and anchors the heart of this loving pastor/father.

We often try and separate Christ's mercy from his judgment but Paul will have none of this. So why was Paul shown such scandalous mercy? Verse 16:

I was shown mercy so that in me, the worst of sinners, Christ Jesus might display his perfect patience…

Or as John Stott puts it clearly, “because God is a merciful God6.”

Again mercy is not abstract.

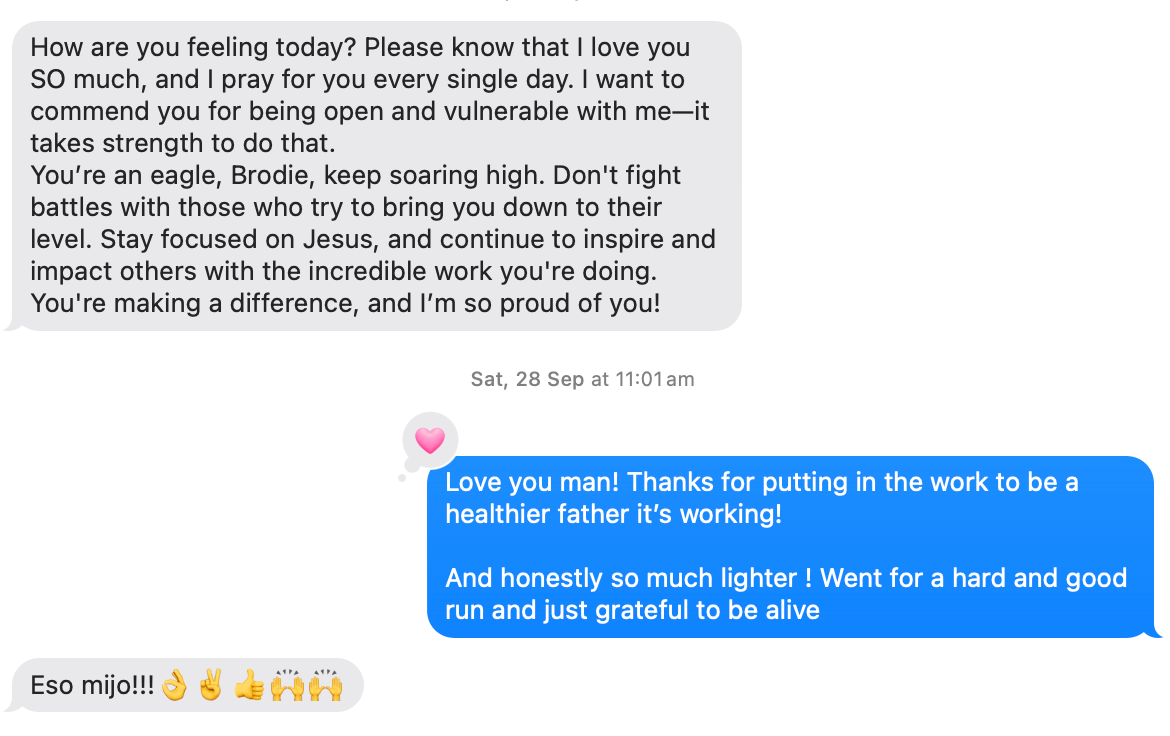

Mercy sees a wounded afraid little boy in the eyes of a man who’s risked it all again and again.

Mercy weeps and gives and gives and then gives some more.

Mercy unfolds rivers of forgiveness to the most wounded and afraid.

Mercy is Christ embodied through a friend who’s been there and done that and now hugs you when you are most whimpering and afraid.

Mercy is Christ holding the most depraved and broken and addicted amongst us.

Mercy is Christ extending a hand to the cheater, the liar, the thief.

But the irony of mercy is that to accept it, one must first admit their lack, their need, and their inability to heal themselves.

Because mercy extends an invitation to healing and humanness. As Stevenson puts it: “We have a choice we can embrace our humanness, which means embracing our broken natures… or we can deny our brokennes and as result, deny our humanity.”

Like Paul, I need mercy - I am too clever and deceitful - I need mercy I am a professional curator - I need mercy for I am a sinner who thinks he’s too well-spoken and gifted to need saving.

I need mercy because I am that scared and wounded little boy.

And this is good news to saved sinners. As the ragamuffin poet Brennan Manning reminds us:

For Ragamuffins, God's name is Mercy. We see our darkness as a prized possession because it drives us into the heart of God. Without mercy our darkness would plunge us into despair - for some, self-destruction. Time alone with God reveals the unfathomable depths of the poverty of the spirit. We are so poor that even our poverty is not our own: It belongs to the mysterium tremendum of a loving God7.

Think of parts of yourself you despise most, the people in your world you can’t stand, the political views you despise - this is where mercy is most needed. For “the power of just mercy is that it belongs to the undeserving. It's when mercy is least expected that it's most potent8.”

1 Timothy 1:16 CSB 2017.

Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: a story of justice and redemption, (London: Scribe, 2014), 17.

Krista Tippett, “Bryan Stevenson: Finding the Courage for What’s Redemptive,” on On Being with Krista Tippett, podcast November 4, 2021, https://onbeing.org/programs/bryan-stevenson-finding-the-courage-for-whats-redemptive/.

Tippet, On Being.

John Stott, The Message of 1 Timothy and Titus: The life of the local church, (London: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 15.

Stott, 1 Timothy, 28.

Brennan Manning, The Ragamuffin Gospel, (Colorado Springs: Multnomah Press 2005), 38.

Stevenson, Just Mercy.